- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

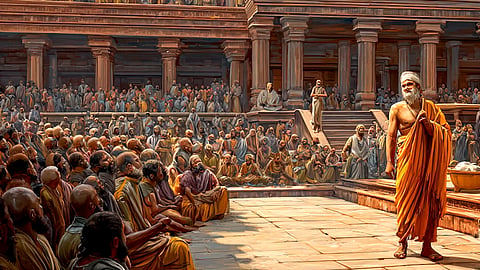

IN THE 18TH CENTURY, Amatya Ramachandra Pant, Chhatrapati Shivaji's Finance Minister, authored an encyclopedic Ajnapatra (Royal Edict). It was a rather extraordinary user manual detailing every minute nuance of statecraft and administration. Shivaji’s grandson, Sambhaji II consulted it for guidance on all administrative matters.

Two things are notable about this document: first, it is loosely modelled after Kautilya’s Arthasastra, a work of original genius; second, it shows the awesome civilizational continuity of Bharatavarsha in the realm of statecraft, politics and administration.

I cited the Ajnapatra to illustrate the aforementioned continuity — from Kautilya to Shivaji. Be it the organisation of the state, the names and functions of administrative departments, fixing salaries of employees, defining juridical precepts and practices, elucidating customs, manners, and traditions of various communities, the Ajnapatra, like the Arthasastra, is a fine example of this continuous flow of the Sanatana institutional heritage.

The reason this heritage remained unbroken is because its foundation was Darshana or philosophy and those who revealed the Darshana were considered as Rishis. To understand this in another way, Arthasastra or Rajyasastra was primarily a Dharmasastra and the institutions it birthed were ultimately meant to uphold, protect, propagate and fight for Dharma. The aforementioned B.A. Saletore beautifully explains how and why Arthasastra was a subset of Dharmasastra.

“From the wide range of subjects covered by the term dharma…which stretched from law to piety, it is obvious that the Dharmasastra regulated… practically all matters of public behaviour which had a vital bearing on the progress of society. These considerations would justify our assumption that the Dharmasastras formed essentially a universal code of righteous conduct for all…” [Emphasis added]

In both theory and practice, traditional Hindu political institutions were characterized by completeness and integrity as an entire system incorporating public and private law. The integrity was derived from both the theory and practice of just one philosophical conception: Dharma. This is precisely what makes the Hindu political and legal system rather unique from the rest of the world. Mahamahopadhyaya P.V. Kane’s pithy words are worth quoting in this regard:

The Dharmasastra authors held that Dharma was the supreme power in the State and was above the king, who was only the instrument to realize the goal of Dharma. To these authors the State was not an end in itself but only a means to an end.

We can also assess its importance and impact from what is known as the “relativity” principle: i.e., how the ancient Hindu institutions can be understood relative to a specific region in Bharatavarsha or in the context of specific empires and periods in our history. This relativity also helps us to get an accurate grasp of the Hindu political, social and cultural evolution throughout the history of India.

In this background, let us look at some practical examples from our history that illustrate these points.

THE OBVIOUS PLACE to begin our journey is by tracing the evolution and operation of Hindu political institutions. At the top was the kingdom or the empire as an integrated or unified whole, headed by the Samrat or Chakravartin or Maharaja. He was assisted by a council of ministers numbering eight or sixteen or even twenty-seven in some cases.

The word Rajan (or King) means one who can keep the people contented and happy: Ranjanaat Raajah. Power and authority vested in the king implicitly rested on the sanction, goodwill and consent of the people. The ultimate right of the people—or collective will—as the sole arbiters of the kind of government they wanted was recognized. This recognition was given concrete and practical form in two restraints on the power of the King:

1. The primacy and supremacy of Dharma as the guiding force of the State…i.e., the king was circumscribed by Dharma.

2. The counsel of the Wise people whose gentle but firm persuasion kept the king from committing excesses and from becoming a despot.

This underlying political philosophy is precisely what gave birth to some of the most enduring political institutions in Indian history. Our people implicitly obeyed the ruling class because the ruling class was afraid of being perceived as someone who violated Dharma.

In the Vedic era, the election of the king was in the hands of the citizens. Every village, town and city had public halls (akin to the modern Town Halls) where people would regularly meet to discuss issues of public importance. These halls also served as the location for general social gatherings and functions. Vigorous debates were held; both local and non-local issues were sorted out after heated discussions that sometimes lasted for weeks. These halls were also venues for verbal contests. The Tattiriya Brahmana has a brilliant verse which encourages young men to actively participate in public assemblies and speak their mind on social and national issues without fear. One mark of distinction of a young man was his participation in and contribution to social and public issues.

The King studiously compiled reports of all such debates and generally followed the current of public opinion. More importantly, he would consult the prominent and wise people in his kingdom before implementing a policy that he felt would go against public opinion.

The classic example is Dasharatha, who invited the heads of all the villages in his kingdom and placed his proposal in full public view: do I have your consent for nominating Rama as my successor? After they heard it, the chiefs went away and formed a separate assembly to discuss the matter in detail. Here, they dissected Dasharatha’s proposal threadbare by discussing Rama’s qualities, character, and competence, and compared notes with one another on what they had heard about Rama. Finally, they reconvened before Dasharatha and said they had no objection to Rama’s nomination. The gratified monarch and father said to them with folded hands, “I humbly accept your verdict.”

We see the same example in the case of Janaka and Yayati who sought public sanction for major and minor decisions. Let’s also not forget that other tragic episode in the Ramayana… Sri Ramachandra renounces Sita Devi precisely owing to the opinion of one citizen. That also counted as public opinion.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.