- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

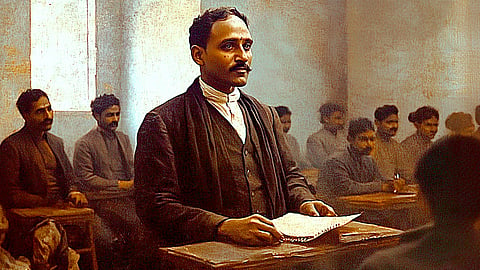

FIRST, WE SHOULD make sure that our pupils understand what they take down from our lips. I occasionally set a day apart when the boys bring to the class their manuscript copies of my notes after marking every place where they have missed a word out or have taken down something which appears incorrect or obscure to them. These, I correct or explain in the class and as boys of the same standard have a curious sameness of errors, the correction of one boy’s mistakes often benefits many others. In this way much useful work can be compressed into a few hours only.

Secondly, the boys should he made to write their own summaries and, bring them to the teacher for correction. These summaries need not cover the whole course, but should deal with the portions left untouched by the professor in his own notes. He need not correct the summaries of all of his pupils from end to end, for he cannot possibly have the time to do it; but even if he corrects a part and clearly puts before the whole class the mistakes he notices, it will benefit them greatly; his pupils will understand the principles of the work, and the majority of our boys can be thereafter left to do the work, without our supervision.

Summaries if made by a student himself serve many useful purposes; the exercise teaches him to separate the wheat from the chaff in what he reads, to marshal facts, in their natural sequence or in the order of their importance, and to practise terseness and accuracy of expression. Above all it calls forth his intellectual self-reliance.

Then, we must encourage our pupils to read freely instead of pinning them down to a particular book or set of notes. Such a course would develop their thinking powers and not merely the memory. It would infuse life and interest into history instead of making it what so many of our average boys believe it to be, a dry catalogue, of dates and names. Character sketches, anecdotes, and historical personages enliven the study and raise it above drudgery. College students must also be made to rise above mere, narratives and should be impressed with the philosophy of history; they should be told the why of past events and the how of past lives.

Happily, most of the recently published historical textbooks do this and the professor should recommend such works for private study by his pupils.

Then, again, even in the lowest classes, it is good to bring the latest results of research to the knowledge of our pupils. I have found that they take an interest in such things when put in a popular and lucid form, and these have a very stimulating effect on their minds by rousing their curiosity and setting them thinking.

We should try our utmost to make the historical past live again before the eyes of our boys. Hence, we must have maps, relief maps, wall-pictures of historical scenes, personages, costumes and arms and coins and antiques in the class-room.

In putting these suggestions into practice, we must first answer the question: how to induce our boys to read? My experience is that it is a mistake to recommend a big book like Tout’s Advaneed History of Great Britain, 727 pages of small type, to ordinary Indian freshmen of the age of sixteen. They cannot, they will not read it through, even though it gives very full and up-to-date information on the history of England. They can be fairly called upon to read select passages or even chapters in a large and popularly written history, for addition or embellishment to the ground-work of their knowledge. But a huge volume like Tout cannot possibly be the main source of information to them.

I have, therefore, asked my pupils of the 1st year class to read some smaller book like Kansome, Gardiner ot Edith Thompson and supplement and correct these works in the light of modern research. Here the professor’s notes come, usefully in. This is the only means I have found practicable for dissuading our boys from relying on printed or dictated summaries of the whole course in History.

Another experiment in education which I have made with great success at Patna College is, what may be called the Vernacular Seminar. Early in the term I put up a list of subjects, with sources of information (in English) and ask my B. A. students to read them up and write vernacular essays, two students taking up a subject. The writers have to give exact reference to authorities, criticise evidence, and make at least an attempt at freshness of thought, instead of producing a mere epitome of the sources. The essays are read by the writers in the full class, and the professor concludes by criticising them and supplementing their information.

The advantages of this plan are obvious. First, we get rid of the language difficulty mentioned before; the students write as easily as they talk in their mother tongue. There is no chance of their repeating catch phrases or words from English books without understanding their meaning. The intellect is here exercised and not the memory. What they have studied and embodied in their essays has truly become a possession of their minds; it is an addition to their real knowledge.

The habits of original thinking, of presenting old facts in a new light, and of deducing the philosophy of history, can be developed only by such a system. Moreover, the boys learn how to handle authorities and discriminate between them according to their relative value, instead of looking upon all printed words as gospel truth.

The habit of selection and orderly arrangement of facts is thus taught, and young men who have gone through such a training are not likely to be appalled by the sight of a big book ,—but they know how to skip what is unnecessary and study only what is essential for their purpose.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.