- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

Mirza Ismail: Former Diwan of the Mysore Princely State

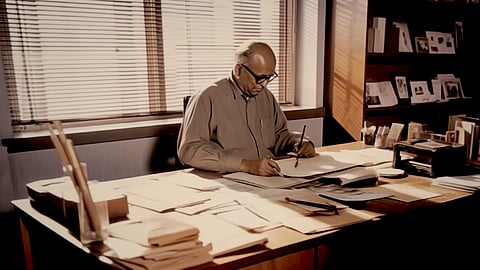

D.V. Gundappa: Honorary Secretary, Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs

B.D. Jatti: Former Chief Minister, Government of Mysore

G.B. Pant: Home Minister, Government of India

B.N. Jha: Secretary to Govt of India, Ministry of Home Affairs

Fateh Singh: Joint Secretary to Govt of India, Ministry of Home Affairs

RUMMAGING THROUGH ARCHIVES yields unexpected harvests especially when one is on a quest for something totally unconnected. That is how I found three acerbic letters that the iconic D.V. Gundappa (one of the guiding lights and guardian angels of The Dharma Dispatch) wrote in January 1959. The three letters are actually variations of one letter, which triggered a flurry of correspondence between the Union Home Ministry and Government of Mysore. Running into about sixteen pages, the exchanges are as good a specimen as any of the agonising rigmarole also known as the Indian bureaucracy. A rather straightforward issue that DVG had raised birthed an entire file — twenty-two pages thick — replete with notings and rules-quoting, and evidence of precedence and references and appendixes and back-and-forths between ministers and secretaries and joint secretaries. A simple matter that took four months to reach a closure.

It all began with the death of the former Diwan of the Mysore Princely State, Mirza Ismail on 5 January, 1959. Mirza was one of the longest-serving Diwans of Mysore (1926 — 1941). His tenure was tumultuous to say the least but to the extent he could, he had upheld the dignity of that high office.

On various occasions, Mirza and DVG were driven apart by serious differences. Yet, till the end, both had mutual respect and affection as men genuinely devoted to public life. They never allowed differences to descend into hostility. DVG’s excellent, detailed profile of Mirza is truthful, nuanced and moving.

But Mirza Ismail had died in an India that was rapidly becoming unrecognisable to people of his vintage. In the twelve years after India attained political freedom, the old decencies and informal courtesies that had been a way of life in Indian politics during the last century had corroded. With the abolition of the Princely States, the Congress had emerged as a monster worse than the imperial British. Its long-held contempt for our Rajas and Maharajas and Diwans and Bakshis was visible throughout the 562 (former) Princely States. This class of erstwhile royalty was now compelled to bow down before sleazy Congress opportunists and phoney freedom fighters.

And so, Mirza Ismail’s death hardly mattered to this burgeoning tribe of Congress ingrates. The then Mysore Government didn’t even think it appropriate to mourn his death even in the time-honoured fashion: of declaring a holiday for all Government offices.

It was this ungrateful conduct that irked DVG. On 11 January, 1959, he sent an angry letter to the Chief Minister to the Government of Mysore, B.D. Jatti. The letter is reproduced in full:

“Sir,

I consider it my duty, as a public man, to bring to your notice that a very large number of people have expressed to me their dissatisfaction that the Government or Mysore have not shown due respect to the memory of the late Amin—ul—mulk Sir Mirza Ismail, formerly Dewan of Mysore, on the recent occasion of his death. In the view of the scction of the public on whose behalf I am writing this, and whose number in my estimate is a very large one, Government should have declared Wednesday the 7th January a general public holiday, at least out of regard for public sentiment.

I cannot think that the present Chief Minister of the State is unaware of the worth and work of his great predecessor in office. I have listened to the tribute paid by him to Sir Mirza Ismail in a radio talk.

How the public at large felt about the death of Sir Mirza was evident from the vast thronging crowds that lined the route of the funeral procession from Sir Mirza‘s house to the faraway cemetery.

I do not know whether the Chief Minister or any representative of his or the Chief Secretary to Government was present in the funeral procession. I saw Mr. T. Mariappa, Finance Minister, in the procession, and Mr. Kadidal Manjappa on the cremation ground. It seems to me that it would be proper courtesy if representatives of Government as such associate themselves with demonstrations of popular sentiment in connection with the death of one who undoubtedly contributed much to the prosperity and prestige of the State. My recollection is that, when previous Dewans died, — from Sir K. Seshadri Iyer downwards, so far as— I can remember;.— public holidays wore declared and a Gazette Extraordinary was issued, recording appreciation of the services of the deceased administrator.

I need hardly say that I am not here concerned with law and rules. My concern is only with what would be proper form in public life. A Government should make it clear that it shares the popular sentiment on great occasions.

When a public man is dead, what counts in countries like England is his general worth as man and citizen, and not his party or his views on specific issues. Such occasions, whether of condolence or of congratulation, are made use of for taking off the acerbities of political controversy and emphasising the bonds of national unity.

With deep respect, I remain, Sir,

Yours faithfully,

(D.V. Gundappa)”

THEN DVG WROTE one more letter to Chief Minister B.D. Jatti the very next day, 12 January, 1959. The reason: he had read a news report published in The Hindu, quoting Jatti’s speech about Mirza Ismail’s death. The Chief Minister’s speech had rubbed chilli powder on the open wound. Just as DVG had already anticipated in his previous letter, Jatti had, in a press conference, thrown the rule book, which apparently prohibited such displays of Governmental mourning. Let’s read it in DVG’s own letter to the Chief Minister:

“Sir,

In a letter of yesterday No. 341/59, I ventured to write to you about the sentiments of a large body of the public regarding the Government of Mysore‘s attitude towards the memory of the late Sir Mirza M. Ismail, former Dewan of Mysore. After signing that letter, I have seen the ”Hindu” paper‘s report of a statement by you on the subject, made in the course of a press conference on the 10th.

The statement is as follows:

"The Government of Mysore had the highest regard a for Sir Mirza, who had done meritorious service to the State, but the closing of offices and grant of holidays were governed by certain instructions issued by the Government of India and the State Government only followed these rules.”

I beg permission to observe that this explanation has caused me much surprise. It should be an extremely difficult position for the Government of Mysore if, even in a matter of this kind, they had to take instructions from Delhi. In a regime of Responsible Government, one would think that the responsibility of the Government lay towards its own people in the first instance. What the state of public feeling in Mysore is on any occasion is best appreciated by the Government in Mysore, and not by the Government in Delhi.

When that is so, it should be an extremely anomalous position if Delhi were claiming superior authority for action on an occasion of this nature.

I do think there is need for a revision of the terms of political relationship between Delhi and Bangalore at least as regards public holidays. I am therefore forwarding a copy of this letter to the Minister for Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi, for consideration and trust it will be viewed with sympathy.

With deep respect,

Yours faithfully,

(D.V. Gundappa)

What happened next will be narrated in the next episode of this series.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.