The Art of Reading - An Instructive Lesson from DVG

Editor’s Note

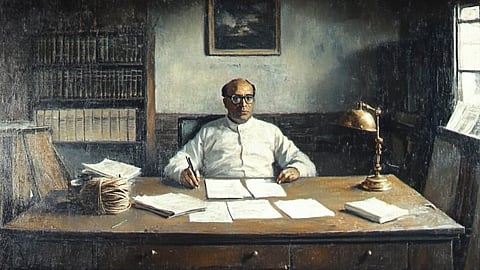

THE FOLLOWING IS the full text of a marvelously instructive essay written by the iconic D.V. Gundappa way back in 1915 in the December edition of his Karnataka biweekly. It characteristically reflects his love of the written word and his abiding pursuit of all noble and elevating literature.

I think it is timely to revisit the essay given the heedless pursuit of Artificial Intelligence in our own time. I view the usage of dangerous tools like ChatGPT as Saraswati Droha — betrayal of Saraswati, the Goddess of Learning. From a larger perspective, the emergence of ChatGPT and its variants is the outcome of the wholesale dumbing down of the global society. This dumbing down, in turn, is the consequence of the downfall of reading. A well-read man, until recently, was regarded as a national asset.

There is reading and then there is reading — deep, sustained and even meditative reading. The well-read man was one who had combined all these three traits in him. This mastery came only from dogged and sincere effort lasting years, and once it was achieved, it lasted for life. Thus, reading is both effort and art.

In this essay, DVG beautifully delineates the method of transforming reading into an art.

It is my ardent hope that the readers of The Dharma Dispatch will find value in this essay and pass it on, most importantly, to their children.

Happy reading!

The Art of Reading

READING, BACON TELLS US, maketh a Full Man. But, mark you, a feeling of fullness is ofttimes a symptom of indigestion. If, therefore, we would guard against mental indigestion, we must look to the matter and the manner of our reading; we must be careful what we read, and likewise how we read.

Literary dietetics is complicated by the ever-extending menus of the publishers. There is such an over-abundance of books nowadays that it becomes more and more difficult to pick out those which are most worth reading. And this same plethora of books, although it cannot be said to make it less easy to know how to read, certainly makes it harder to observe the approved precepts of the art of reading.

More books are written today than ever before, and, presumably, more books are read than in former times; yet every one complains that he has no time or insufficient time to read. The bookworm laments that he cannot consume his whole library of classics, let alone lighter fare.

The man who is drawn to other pursuits, outdoor and indoor games and hobbies, explains that he unfortunately has little leisure for books, solid or otherwise. Few, if any, can find enough time for reading; and in a vain attempt to make good the deficiency, too many of us are prone to skim books instead of reading them or to select for perusal such volumes as can be finished most speedily. Such volumes, in other words, as are most unreadworthy. For a good book can seldom be read quickly and ought always to be read slowly.

To learn to read, says M. Faguet, the most eminent of living French critics: “You must first of all read very slowly and next you must read very slowly and always down to the very last book that has the honour of being read by you, you must read very slowly.”

We quote from a charmingly written and most instructive little volume L’art de Lire. In this work M.Faguet gives a series of Causeries on the Art of Reading for pleasure’s sake… The art of reading, says M.Faguet, is the art of thinking with a little assistance:

“consequently, it has the same general rules as the art of thinking. One must think slowly. One must read slowly. One must think with circumspection, without giving free rein to one’s thoughts, putting one’s self-objections all the time; one mustread with circumspection constantly confronting the author with objections. Yet one must, to begin with, abandon oneself to one’s train of thoughts, and only turn back to discuss it after a certain time, otherwise one would not think at all; one must repose confidence for the time being in one’s author, and only ply him with objections after one has a made certain that one understands him aright; but then put him every objection that occurs to you, and examine carefully not only whether he has not actually made reply, but also what he might say in reply thereto. And so on, for to read is to think with another, to think the thoughts of another, to think the thoughts, like or contrary to his own, which he suggests to us.”

It was very much the same advice that Bacon gave when he wrote three hundred years ago: “Read not to contradict and confute; nor to believe and take for granted; nor to find Talk and discourse; but to weigh and consider.”

The weights and measures…will not be the same for every type of work. There are very few precepts of universal application in the art of reading. You cannot read a philosophical work in the same way as a romance, a poem in the same way as a text-book of political economy, a play in the same way as an essay.

Each must be read in its own appropriate fashion. A play, for instance, must be read as a play — a piece for representation, though robbed of the glamour of the footlights; you must visualize the characters and the scenes; you must see and watch with the mind’s eye the stage and those upon it, noting their exits and their entrances, their attitudes and all their doings; you must pick out the author’s mouthpiece and distinguish the dramatist’s own natural style from the style he invents or borrows for each of his creations.

The two principles we have stated — read slowly, read critically — is easier to lay down than to carry out in an age which has made a fetish of speed. But they are as fundamental in the Art of Reading as are slow eating and careful chewing in the art of feeding.

Now, if present-day conditions so militate against leisurely and deliberate reading, dare we advance a third general rule which makes a further demand on the reader’s overtaxed time — Re-read? Still this rule is no less important than the other two. By re-reading, M. Faguet reminds us, we learn the art of reading. And what is more, to re-read is to re-live.

“In re-reading you compare yourself with yourself, you note the rises and the falls of your sensibility; the losses and the gains of your general intelligence and your critical faculty, and thus you trace the curves of your life, moral and intellectual …

“An autobiography might very well be written with the comparative impressions of one’s reading, and might be entitled ‘On Re-reading.’ To re-read is to read your own memories without taking the trouble to write them. If your author is difficult, re-reading is indispensable. If your author seems easy, re-reading nonetheless reaps a rich aftermath. A good book is like gold-bearing quartz; by the first process you only extract a certain percentage of its precious contents; further treatment secures a notable addition to the yield.

“Some good books demand, all good books repay rumination. To re-read is to chew the cud, to digest the otherwise indigestible. It may be somewhat slow, even arduous work, but its reward is exceedingly great.

“And as Thoreau says: “To read well, — that is, to read true books in a true spirit, — is a noble exercise and one that will task the reader more than any exercise which the customs of the day esteem. It requires training such as the athletes underwent the steady intention almost of the whole life to this object.

“Books must be read as deliberately and reservedly as they were written.”

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.