- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

After he began the work of the Pratishthana, Sri Sheshanna Shrauti did not undertake other activities outside of this. Night and day, day and night, he labored on akin to a penance. In a way, he was a one-man institution. Contemplation, analysis, research, writing—he accomplished all of this singlehandedly. Of course, others assisted him on rare occasions. But given the nature of his work, this assistance was really insignificant. As far the institution’s finances were concerned, most of the money came from his family, relatives, friends, and well-wishers. The general public’s contribution was next to nil.

Once the Bangalore branch of the Arya Samaj requested his permission to use his translation and commentary on the Sama Veda Samhita in their translations of the Vedas. However, Sri Sudhakar Chaturvedi and others refused to include Sayana’s commentary [on the Sama Veda]. Therefore, Sri Sheshanna Shrauti had to withdraw from the project. He had boundless reverence for Sayanacharya. Despite this, Sri Sheshanna offered his unstinted assistance in various ways to the Arya Samaj’s efforts at publishing the Sama Veda volumes. As always, he refused to put his name to it.

This caused a bit of consternation in me. Each time I raised this topic with him, he used to say, “They have their own system. They are also serving the Veda Purusha in their own way. Why should we be upset with them? What you say is true. However, in some cases, courtesy is greater than truth.” I could never make Sri Sheshanna’s equanimity mine.

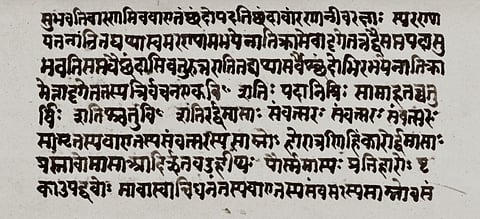

The work of the Pratishthana progressed with great aplomb. Eventually, a superb torrent of books were published one after the other. This included every single work on Sama Veda’s Purva and Apara Karmas and Prayoga. Every work contained Mantras with their Swaras, detailed explanations including traditional commentaries, the background and relevance of every Prayoga, nuances and differences of Deshachara [rituals, practices, customs and traditions unique to a particular geography], and comprehensive research material. On the surface, these works dealt with Prayoga. In reality, they were mini-encyclopaedias related to the Karma Kanda of the Sama Veda. Equally, these volumes are not merely restricted to the Sama Veda but are applicable and relevant to all Vedas. They’re also definitive and intimate volumes for anybody interested to learn about Santana culture.

Sri Sheshanna Shrauti displayed the same rigour, completeness, and orderliness in bringing out the complete Sama Veda translation in Kannada along with the traditional commentaries. The preface itself runs into a whopping 300 pages! It is a veritable treasure of dollops of valuable material and insights. He has given evidence to each item right at the place of their occurrence. Additionally, he has prepared an alphabetical index of Mantras. Each Mantra follows a sevenfold explanation: the Rk, Pada-pata, differences in chanting, Sayana’s commentary, word-by-word meaning, overall summary, and poetic translation.

In this monumental task, the role of his son, daughter-in-law, relatives, and well-wishers in painstakingly composing thousands of pages and proofreading the manuscript is truly memorable. Error-free printing, simple but meaningful cover page, and extremely affordable cost—these are the other great qualities of the volumes. This is a noble and unparalleled adventure that is easily comparable to the world famous Rg Veda volumes that the late Mysore Maharaja sponsored. However, it is tragic that only a handful of people, even in the scholarly world, are aware that these volumes exist. One can only say that this is the sorry fate of our country.

A few years after I wrote Sandhyadarshana, I expressed my wish to further revise various aspects of our Karma-Kanda and to separate the superfluous and unnecessary elements therein and make it more accessible to the current times. He not only encouraged my effort but offered his valuable insights and suggestions. In one such discussion, I raised an objection related to our weddings and Upanayanam. I said that there were copious amounts of wastage and extravagance in these occasions and that the Purohitas were prescribing all sorts of needless procedures, etc. Sri Sheshanna said:

“What you say is correct. However, without a certain degree of splendor, how can the full glory of each ritual touch our heart? No Apastambha or Ashwalayana[i] has prescribed that womenfolk should wear grand saris, deck themselves up with ornaments, adorn themselves with beautiful and fragrant flowers and create an atmosphere of soft exuberance as they walk around the wedding hall. However, without all this splendor, there will be no difference in atmosphere between a wedding and a funeral in the eyes of the proverbial common folk. Therefore, when you are revising these rituals, please pay attention to the sentiments, customs and practices of the common people.”

After listening to him carefully, Sri Sheshanna’s intent and spirit convinced me that he was right. In recent years, this conviction has only grown. Besides, the Dharmasutra and Grihyasutra authors have themselves proclaimed, “atra gramavruddhah prashtavyah,” meaning, the words of the aged women and men of the village are to be taken as the final arbiters in deciding matters of routine conduct, customs, traditions, and rituals. As Bhagavan Buddha said, Sanatana Dharma is “bahujana hitaya bahujana sukhaya,” meaning, one goal of Sanatana Dharma is the welfare and happiness of the masses. It is only Santana Dharma that is accessible to everybody, satisfies everybody, and among the masses, it affords the choice, freedom and comfort to those who wish to elevate themselves spiritually. No other religion has this profound and all-encompassing quality. The intent of people like Sri Sheshanna Shrauti was to strive precisely towards these ideals.

Sri Sheshanna was vexed with the widespread propensity among a good section of Hindus to compulsorily find spiritual or supernatural meaning in every letter of the Veda. This propensity came at the expense of completely ignoring the beauty of its Adhiyajna meaning. Sri Sheshanna thought that it was incorrect on the part of luminaries like Swami Dayananda Saraswati, Sri Aurobindo, Sri Kapali Sastri et al who forcibly discerned spiritual meanings in every Mantra of the Veda. However, he did not take a stern stance on such impositions.

On this subject, I once told him,

“Spiritual meaning is akin to the nectar inside a flower. Even if you collect it from hundreds of flowers, its sweetness is the same, its quantity is also little. However, the Adhibhautika, Adhidaivika and Adhiyajnika levels of meaning are not like this. They represent the entire gamut of elements like the plant, creeper, branch, shoot, leaf, flower, petal, form, shape, colour and fragrance in an extraordinary fashion. There is no doubt that the ultimate meaning of the flower lies in its nectar. However, there’s absolutely no need to condemn the overall beauty and value of the entire plant and creeper in this quest. The maturity, fulfilment and fruition of worldly life is totally different. At least to our extent, this fruition will not reveal itself in a void. The Ishavasya Upanishad proclaims this exact truth in, ‘avidyaya mrityum tirtva vidyaya amrutamashnute’ and other mantras.”

When he heard this, Sri Sheshanna Shrauti was extremely delighted. Not only that, he also made me write a foreword to one of his Sama Veda volumes that conveyed this sentiment. His entire life was a commentary of this profound truth.

To be continued

[i] Apastambha and Ashwalayana are two prominent authors of Dharmasutras and Grihyasutras

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.