- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

Ever since we published The Story of Kelambakam, we have received substantial positive feedback urging us to publish more valuable material about this tiny Sanatana village that existed and flourished in the early decades of the twentieth century. As we noted in that introductory essay, Kelambakam has today been heartlessly gobbled up by the forces of modernity, “development,” “progress” and the rest.

Bowing to public demand and from our own conviction to preserve all that is great and valuable in the Sanatana heritage in our own humble way, we begin a series documenting several heart-warming and profoundly moving vignettes from life in Kelambakam as it was lived just a century ago.

From the time they set their soiled feet in Bharatavarsha, almost all European travellers were amazed and stunned at the gentle and calming influence that the ubiquitous Purohita wielded on the Sanatana society. One such traveller recorded this amazement as follows:

By the strength of his intellect the Purohita has moulded the thoughts and guided the feelings of the people to such an extent that a foreign observer may well stand amazed at the result.

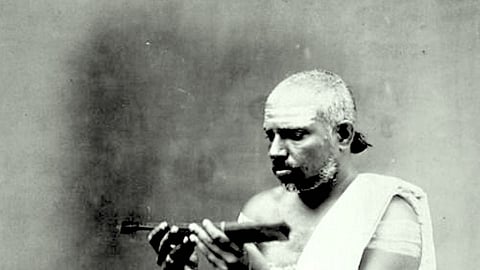

The Purohita of Kelambakam was Ramanujachariyar, the friend, guide and philosopher of the village. His influence over the villagers is very great. He is a venerable old gentleman aged over forty, well versed in the Hindu Shastras. He knows a little of Sanskrit and has read many books on astrology. He could repeat by heart all the four thousand stanzas of the sacred Prabhandham, usually called the Tamil Vedas. He is considered by every villager as part and parcel of his family, and the simple villager dare not do anything without consulting him.

Ramanujachariyar owns a house near the village temple. It has a decent appearance. On the floor near the entrance are quaint Rangolis drawn with rice powder, representing various deities and shapes and figures. On the wall facing the street are seen representations of the coronation of Rama, of Krishna tending cattle and playing the flute, of Narasimha killing the giant demon-king, and many other figures which at once convince the stranger that the occupant of the house must be a person steeped in Dharma and devotion.

The old gentleman rises very early in the morning, bathes in the tank, puts on the usual sacred marks on his forehead and other parts of his body, performs the Puja and returns home.

He then sets out with a cadjan (palmyra leaf) book, which is the calendar for the year, and first goes to the house of the village munsiff Kodandarama Mudelly (Modalali). The munsiff, as soon as he sees the Brahmin, rises and salutes him, and asks him to take a seat. The Purohita opens his book and reads from it in a loud voice the particulars of the day, the year, the month, and the date, the portions that are auspicious and those that are not, etc. While this recital goes on, the munsiff is all attention.

Soon after, an old woman, the mother of Kodandarama Mudelly, steps in and asks the astrologer on what day the new moon falls, and when the anniversary of the death of her husband should be celebrated. On many occasions, the munsiff asks him if, according to his horoscope, the year will on the whole be a prosperous one for him and if his lands will bring forth abundance of grain. To such questions, the Purohita answers according to the rules of astrology.

After this, the Purohita goes to the house of every villager and various questions are put to him. One villager asks him to appoint an auspicious day for buying bullocks to plough his fields; another asks him to name a propitious hour for commencing the building of a house; a third asks him to select a day for the marriage of his daughter and shows him the horoscope of his would-be son-in-law; a fourth asks him to fix a day on which to go to the neighbouring village to bring his daughter-in-law home; a fifth asks him when such and such a feast comes; a sixth puts into his hands the horoscope of his sick son and asks him if he will recover; a seventh requests him to prepare the horoscope of his newly-born child and furnishes him with the exact time when the child first saw the light of day; the next person complains to him about the loss of a jewel, and asks him to name the person who stole it, to describe the place where it is hidden, and so on.

To all these questions, the Purohita, opening his book, gives suitable answers, and, to illustrate his statements, he quotes Sanskrit slokas, stanzas from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Divya-Prabhandam, and verses from works on astrology. These quotations create extraordinarily strong impressions on the minds of his listeners and give them succor and hope. As an old writer remarked:

In the East, wisdom is held to consist, less in a display of the sage's original talents, than in his ready memory, and happy application of the sacred writing.

The instructions of the Purohita are obeyed by the villagers to the very letter. The farmers will not begin to cultivate, to sow their lands, or to reap their harvest without first consulting him as to the auspicious time.

The Brahmin also officiates as priest on marriage and funeral occasions, and is the Principal during feasts, which are of almost daily occurrence in a Hindu family. There is a Tamil proverb which says: “ The Vaidyan or the doctor will not leave the patient till he dies, but the Purohita will not leave him even after his death.”

Such is a brief description of the old sage of Kelambakam, whose influence even in the neighbouring villages is very great, and whom the villagers regard with feelings of deep veneration.

Apart from the house of the Purohita, there are two other houses near the temple belonging to Brahmins who do work in the temple. In one lives Varadayyangar and in the other his brother Appalacharri. They perform the Puja of the temple by turns, and lead a very simple life. Persons who go to the temple to worship the Deity take with them offerings in the shape of money, fruit, coconuts, betel and nut, etc. A portion of this forms a source of their sustenance.

There are about seven acres of land in the village set apart for the temple, and the income derived therefrom goes towards the expenses incurred for the lighting of the temple, the daily rice offerings, and the salaries of the servants, etc. As the brothers are the principal servants of the temple, they get a share of this income. Besides these, they get extra income on festival occasions, when the Murti is decked with jewels and flowers and carried in procession.

Kodandarama Mudelly is also the Dharmakarta (Chief Trustee) of the temple and is adept at resolving any disputes that may arise. His gentle disposition and courteous behaviour and sober manners have rubbed off on the villagers who are generally quiet by nature.

The next person in importance to the Purohita is the schoolmaster, Nalla Pillai.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.