- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

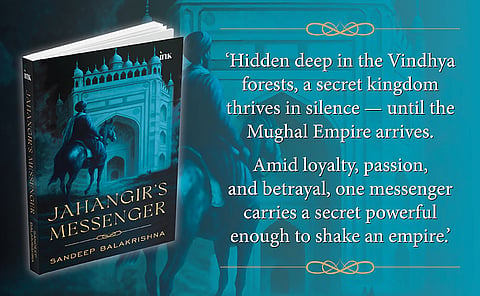

The author of Jahangir's Messenger is the founder and chief editor of The Dharma Dispatch.

THE TEENAGED PADMASIMHA received a thorough education in all the disciplines prescribed for a Kshatriya, and he rigorously subjected himself to it. But as far as he was concerned, this was not merely education. He regarded it as a solid training that would help him to fulfil the lifelong vow of vengeance that he had made to himself. Apart from formal military training, Padmasimha underwent a gruelling course in jungle warfare. He freely mixed with the Aatavikas and earned their trust and became part of their family. He dressed like them in bark and leaves and coloured his body with the dyes of various foliage. He ate their food and drank their drinks and celebrated their festivals with genuine feeling. He assuaged their troubles and became their son and brother. And when the time came for him to depart from Kesaridurg, Suryadeva Simha had composed a moving poem likening it to Sri Krishna’s farewell from Gokula. No matter where destiny took Sri Krishna, no matter where Sri Krishna guided destiny itself, he would, forever, have a fond place in the hearts of the people of Gokula.

After returning to Nadduvala, the first thing that Padmasimha did was to refuse to be coronated. He had the first right to kingship by virtue of being the eldest son. He passed the throne to his younger brother, Vikramasimha. In a solemn ceremony announcing his decision, Padmasimha publicly proclaimed his vow of adopting lifelong Brahmacharya or celibacy. It was the Brahmacharya of Kshatra. Even as a teenager, it was Padmasimha’s unshakeable conviction that the accursed rule of the Turushkas was rooted in fanaticism, sustained by oppression, and it would eventually be lost by the continuous discharge of their energy, wasted in the mindless dissipation of the sense organs.

From then till now, Padmasimha was serving as the Maha-dandanayaka or commander-in-chief of Nadduvala. Anyone who was even remotely acquainted with him equated him with Parashurama himself.

About a month prior to the official coronation, Padmasimha took his younger brother to Chittorgarh. It was not a journey but a pilgrimage.

Chittorgarh.

The ancient Vira-Bhoomi, the warrior city that had unstoppably radiated heroism from every speck, pore, and pebble. And now, it was a desolate, barren graveyard. Not even a widow had survived to narrate the tearful saga of its pointless misfortune. But even if such a widow were alive, which heart was brave enough to listen to her, to bear the woe, to remain sane? Chittorgarh, the bleak, vacant, and deserted expanse of emptiness atop the magnificent fort lay languishing in the noiseless funeral rites performed each moment by the Pancha-Bhootas, the Five Elements. It would perhaps never attain Sadgati.

Chittorgarh.

The pinnacle of the pride and prestige of Rajput power. It had never bent before any Turushka for eons. And then the despicable Mleccha monster, Akbar, descended upon it and transformed it into a grand cemetery. Akbar had won, but true to its unbending tradition, Chittorgarh had lost heroically.

The fort-city was straggled over a spread of five kos. From the top, it resembled the impossible coils of a gigantic python. Now it was almost impossible to imagine that it was the same city that had, just a few decades ago, been a flourishing nucleus of royalty, wealth, and piety. All the temples inside the fort had been ruined beyond repair. The hundreds of homes which housed almost its entire population had been reduced to sooty crannies, wrecked and burnt by the crowbars and the infernal blaze of the hated Mlecchas. Then there was the fabulous Vijaya Stambha, the Tower of Victory, the pride of Chittorgarh. It now jutted up like an orphaned monarch, a mighty Samrat devoid of a kingdom and bereft of his subjects. The voiceless gloom all around was a constant mockery of the Tower of Victory. To its southeast lay the carcasses of the magnificent palace and mansions of the Maharanas of Chittorgarh. They looked like massive abscesses, awaiting the healing touch of a doctor who would never come.

Padmasimha took his brother on a leisurely and detailed tour of the foothills of the fort. When they reached Rampol, the main gate of the dead city, Vikramasimha exclaimed, ‘Ohhhhhh!’ Despite the colossal scale of devastation, Rampol stood defiant in its unyielding sturdiness.

As they crossed the gate and began ascending the fort, Padmasimha, as if in response to his brother’s exclamation, said in a solemn tone,

‘Rampol is the only surviving symbol of what Chittorgarh was. Our people offered undaunted resistance for three months. It was the toughest challenge that the Turushka worm Akbar ever faced in his whole wretched life. The matchless daring and ferocity of our resistance unnerved and frustrated him. Our warriors had one foot in the battlefield and the other in their grave. At the height of his frustration, Akbar vowed that he would uproot the very source of our valour and annihilate every trace of bravery that had made Chittorgarh feared and invincible. Rampol was guarded by an enormous wooden ingress that was as heavy as an elephant and protruded upwards to the sky. Akbar’s searing vengeance consumed this ingress and three others as well. His army pounded them mercilessly, ripping off the hinges, nails, and bolts before burning them to ashes. He smashed the massive war drums stationed atop each bastion to fine pieces … a war drum is the lion’s roar of valour.’

Padmasimha lapsed into silence and turned right. After ascending about a hundred steps, he pointed to the ruins of a modestly sized temple and said,

‘Jagan-Mata Parvati—Mother of the Universe—used to reside there in the auspicious form of Bhadrakali. That heinous Turushka razed it to the ground and smashed her Murti to pieces. Not satisfied, he dug out the sacred stone lamp-post in the Garbha-Griha from its roots. It had offered perpetual Arati to Bhadrakali Mata since the temple had been built. But the vile Akbar was still unsatisfied. He had it transported to Fatehpur Sikri and installed it in his bedroom.’

Vikramasimha slowly turned and watched his brother’s face. He could spot neither fury nor sadness. There was a sort of dreadful tranquillity in both his voice and countenance.

After twenty minutes, they reached the sacred Jauhar Kund. Padmasimha immediately removed his Peta and held it up to the sky with great reverence as if he was making an offering to some invisible Deity. Then he slowly knelt down, placed it on the ground, and performed a Sashtaanga Pranaam. Vikramasimha emulated him. A minute later, the brothers stood up.

Neither spoke for a long time. Unable to bear the weight of the silence, Vikramasimha looked at his brother’s face again. Droplets had filled the basin of Padmasimha’s eyes, stubbornly refusing to ebb. They vanished the moment he blinked. Another minute later, Padmasimha opened his arms wide and slowly turned around on his axis and said,

‘My son, this is a Tirtha-Kshetra. Even after you are coronated as the Rana, make sure that you visit here as often as you can. I trust I don’t need to explain the reason.’

Vikramasimha looked at him from head to toe before falling at his feet. He touched his forehead to each foot with great reverence.

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.