- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

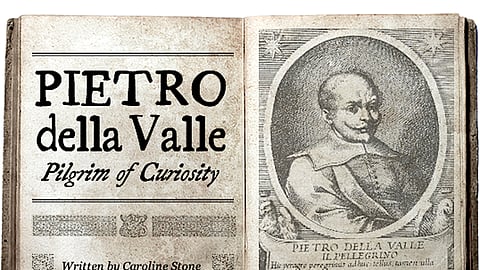

PIETRO DELLA VALLE WAS THE TYPICAL RENAISSANCE MAN. Born to an aristocratic family in Rome in 1586, he acquired a classical education, the standard fare of the era. He mastered Greek, Latin, and epic mythology and became a Biblical scholar. However, his renown rests on his accomplishment as a versifier, composer and musicologist. Much later in life, Pietro Valle earned repute as a prolific author of travelogues and as a fabulous collector of rare manuscripts and books.

His journey as a travel writer was the consequence of unrequited love. We have no information about the lady who spurned him but we know that he contemplated suicide in Naples. His physician friend, Mario Schipano, also became the physician to his wounded heart. He counselled him to travel the world. The idea instantly appealed to Pietro and as a devout Christian, made a vow to visit Jerusalem.

That was the start of an extensive journey that he embarked upon in 1614. He covered Constantinople, Alexandria, Cairo, Mount Sinai, Jerusalem, Damascus, Aleppo, Baghdad, Nineveh, Hamadan, and Isfahan. He took a wife in Baghdad and was treated as a state guest by the Persian king, Shah Abbas. The biting winter of 1620 seriously impaired his health and he decided to return to Italy. The next year, his wife aged twenty-three, died. Pietro was heartbroken a second time. A month later, he was struck by serious illness and collapsed in the city of Lar. However, an exceptionally gifted doctor nursed him back to health.

In the winter of 1623, Pietro climbed on an English ship named Whale, headed to Surat from Shiraz. He would return to Italy via India.

Which is where our story begins.

PIETRO VALLE STAYED IN INDIA FOR A YEAR. But he only sojourned in a small slice of India. He operated mainly from Surat and Gomantaka but travelled for some months along the coastline of Cochin, Kozhikode, Mangalore and Honnavara.

At Honnavara, he was introduced to Vitthala Shenoy, the Ambassador of the powerful Keladi king, Hiriya Venkatappa Nayaka.

This meeting has proven fortuitous for history scholars, researchers and students.

Pietro’s detailed record of his journey into the heart of Venkatappa Nayaka’s kingdom is one of the invaluable primary sources for understanding the political situation of Malnad and coastal Karnataka of the early 17th century.

The overall picture is not flattering.

Political instability, fragmentation and internecine wars among Hindu kingdoms were the hallmarks of this period. Half a century after the annihilation of the Vijayanagara Empire, all its former feudatories are baying for one another’s blood. Hopelessly disunited, they have to singly battle threats from multiple sources including Muslim chieftains and the Portuguese, who have emerged as a formidable power.

Pietro Valle’s meticulous narrative helps us flesh out these political currents. His eye for detail is razor sharp. He misses nothing including the colour of leaves and shrubs and water bodies and hillocks and crevices.

His description of the scenic beauty of the Gerusoppa landscape (home to the world famous Jog Falls) is truly outstanding for its vividness and lifelike quality. We notice the same narrative tenor in his descriptions of its temples, inhabitants, their festivals, customs, and society.

However, there is a cautionary element in this narrative. Pietro was a devout Catholic Christian and his natural bigotry against heathens freely flows in his explanations of Hindu festivals and deities.

Here is a short list of the topics he writes about:

Description of the journey up Gerusoppa river

Ascent of the Ghat

Beautiful scenery

Temple and statue of Hanuman

Female saint

Indian fencing match

Indian torches

Night spent under trees

Myrobalan trees described

One of the charming anecdotes is related to the method of primary education that Pietro witnessed in the Gerusoppa region.

PIETRO VALLE AND HIS ENTOURAGE have taken rest at a fort (now unidentifiable) in the Ghats in Gerusoppa. The next morning, they resume their onward journey to Ikkeri, the capital of Venkatappa Nayaka. Their luggage is being loaded on oxen and Pietro needs to wait for a considerable time till the whole thing is complete.

Having nothing to do, he engages himself by visiting a beautiful Hanuman Temple in the vicinity of the fort. This is what he observes:

“I entertained myself in the Porch of the Temple, beholding little boys learning Arithmetic after a strange manner, which I will here relate.

“They were four boys, all taken the same lesson from the Master. In order to get that lesson by heart and repeat likewise, their earlier lessons and not forget them, one of them was singing musically with a certain continued tone. This has the force of making deep impression in the memory. The boy recited part of the lesson. As, for example, ‘One by itself makes one.’ Whilst he was thus speaking, he writ down the same number, not with any kind of Pen, nor on Paper, but (not to spend paper in vain) with his finger on the ground. For that purpose, the pavement was strewn all over with very fine sand.

“After the first boy had writ what he sung, all the rest sung and writ down the same thing together. Then the first boy sung and writ down another part of the lesson; as, for example, ‘Two by itself make two.’ All the other boys recited in the same manner, and so forward in order.

“When the pavement was full of figures, they erased them with the hand. If need arose, they strewed sand from a little heap which they had before them wherewith to write further. And thus they did as long as the exercise continued.

“They told me, they learnt to read and write without spillling Paper, Pens, or Ink, which certainly is a pretty way. I asked them, if they happened to forget, or be mistaken in any part of the lesson who corrected and taught them? They were all scholars without the assistance of any Master at the moment. They answered me and said: true, it was not possible for all four of them to forget, or make a mistake in the same part of the lesson. Thus, they exercised together so that if one happened to be wrong, the others might correct him. Indeed this is a pretty, easy and secure way of learning.”

What Pietro Valle witnessed in those wild hills of Gerusoppa in the 17th century was simply the time-tested Indian method of learning. Marvellous in its simplicity and an incredibly powerful method whereby what you have learnt stays with you forever. This is precisely what an astonished Monier Williams witnessed and recorded two centuries later. This is how the stalwarts of the Modern Indian Renaissance learned in their boyhood.

It’s pretty tragic that this method has all but disappeared today.

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.