- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

GUILDS AND CORPORATIONS IN ANCIENT and medieval India also functioned as local banks that accepted public money and paid interest in the range of nine – twelve percent. Like any bank, they also lent money.

Larger guilds extended their banking services throughout India. Enough evidence exists to show that there was an impressive network of such banking guilds dotting the entire geography of Bharatavarsha. Their organization was coherent, well-linked and above all, they operated on the basis of strict honesty, integrity, fair dealing, and had a fear of incurring paapa. Measured on the parameters of professional competence, organizational efficiency, customer service, and delivery, these banking guilds can hold their own against contemporary banking systems. This was in an era where plain, simple trust and not fraud-detection software was the norm. Like their compatriot commercial guilds, these banking guilds discharged their share of charity and piety as we shall see.

All of these traits are precisely what inspired trust among the public who deposited large sums of money. Likewise, another significant feature of these corporations was the fact that they had a system similar to travelers’ cheques. Then there was another side to it as well. For example, if a traveler ran out of money in a faraway land, he could take a loan from a local guild and repay it to a guild back in his native town or village. That local guild was in turn connected with the guild from which the traveler had taken out the loan.

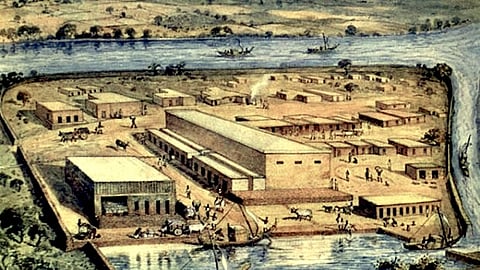

Village and town administrative bodies—similar to municipal councils—also provided banking services and worked closely with all denominations of commercial guilds. Banking guilds were recognised as an important constituent in the municipal government of ancient cities such as Pataliputra, Mathura, Ujjaini, Vidisha, etc. The town corporation or municipality recognized their duties as trustees of public money. These banking guilds received not only cash deposits but also endowments of property.

We will examine how some of these features played out in the real life of the Hindu society throughout our history using hard inscriptional evidence.

A large cache of seals dating to the Gupta Era – roughly the fourth or fifth century CE – was recovered at Basarh (Bihar). A majority of these seals deal with corporations (nigama) of bankers. Others talk about guilds of traders (Sarthavaha) and merchants (Kulika). Interestingly, one seal mentions the name of Dodda, the head of a guild of bankers and traders. Together, they had formed a body resembling the modern Chamber of Commerce.

From here, when we travel down to Lakshmeshwara (Karnataka) two centuries later, we find an inscription dated 725 CE. This talks about the Constitution drawn up for the town of Porigere. Here is what it says: “the taxes of all classes of people shall be paid to the guild of braziers in this town in the month of Kartika.” Clearly, this guild also served as the local bank or treasury.

The Chola period supplies us with a truly spectacular portrait of how village corporations also doubled up as banks and treasuries. The hoard of fourteen inscriptions found in 1893 at the crumbling Vishnu temple makes us go awestruck. Together, they give us a comprehensive picture of the economic facet of village administration in South India. Every activity that generated money was given a dedicated fund. Thus, you had a tank fund, a rice fund, an oil fund, a flower-garden fund, a gold fund and various donor funds. These funds were managed by their respective guilds, which had to make regular deposits with the village assembly at stipulated periods. It is this feature that gave a corporate character to the village assembly (Sabha or Mahasabha). The treasury of the village assembly used the interest from these deposits to fulfill the duties laid down in the village constitution, including performing works of charity.

GUILDS AND CORPORATIONS were also executors of endowments and wills. Given the high degree of trust that these guilds inspired, people fearlessly made perpetual endowments and entrusted these corporate bodies to execute them. In turn, these bodies did this job flawlessly over five, six, and even ten generations. And they did this not merely as a job entrusted to them but out of a spirit of Dharma—that is, by executing the endowments, some part of that Dharma would also accrue to them. This automatically reveals the fact that these guilds were generational and had preserved institutional memory in a manner that can only be described as genius-level.

We need to remember that both the donor and the guild discharging the endowment regarded it as an act of piety and reverence. This is perhaps the most elevating feature of the corporate and business history of ancient India.

On the macro canvas, the intrinsic and inseparable elements of Hindu business history include spirituality, godliness, devotion and Dharma. We have a wealth of records that show how corporations themselves made generous endowments of an astonishing variety: for lighting lamps in temples in perpetuity, for upkeep of temples, for Annadaanam, for celebrating festivals, for providing food and other services to Sanyasins, Buddhist monks, for facilitating Tirthayatras…

I will cite just one hoary example.

A Shaka Prince ruling somewhere in the Sindh region in 120 CE made a perpetual endowment of 3000 Karshapanas for the benefit of Buddhist monks engaged in penance in the caves of Nasik. He entrusted the execution of this endowment to some guilds based in Govardhana! As they say in Hindi, Kahan Sindh? Kahan Govardhan, aur Kahan Nasik? Where is Sindh? Where is Govardhan, and where is Nasik? Remember, we’re talking of the India of 120 CE, or 1900 years ago.

And now we’ve arrived at the final stage of this series. We will close with where we began. With Sri Dharampal’s passionate and sustained appeals for decolonising the Hindu psyche and thereby the Hindu society and civilisation.

A tragic, fatal and ongoing consequence of British or European colonialism was the creation of a deliberate myth that European discoveries and inventions and innovations in science and technology alone had all the power and all the secret keys to unlock the mysteries of the universe. Its companion-myth was that European political systems, social organization, institutional frameworks, and intellectual traditions were the sole repositories of all wisdom in the realm of human civilization.

Quite obviously, these myths could only be sustained on the brute strength of their military dominance and superiority. It was precisely this that made them confidently declare that everything in India’s past was primitive and fit only to be discarded. We must admit that they have phenomenally succeeded in instilling this myth among our own people from the lineage that began in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The 1857 war of independence was the last resistance whose foundational inspiration was wholly organic and homegrown.

One major, if not central component of this myth is directly if not entirely related to the Indian corporate and business life till then. It must be remembered that the British first arrived in India only to trade, i.e., in their essential position, they were supplicants before a vastly superior economic power spread across one of the largest geographies of the world. But absolute political dominance made them spin exactly the opposite story. Thus, inveterate racists like James Mill deliberately invented the fiction that our guilds and corporations were closed entities working in isolation, were fossilized and resisted change, progress and innovation.

The opposite is actually true and we can consider just one tiny bit of evidence that proves this reality. As we have seen throughout this series, our guilds and corporations enjoyed an extraordinary degree of autonomy and received royal protection as well. It was precisely this factor that made India the economic powerhouse of the world for several centuries irrespective of the rise and fall of empires and dynasties.

The fact that Indian products commanded extraordinary premium in international markets for such a prolonged duration is one common sense proof of our innovation, progress and other terms whose definitions are not yet settled.

We have the example of Sri Krishnadevaraya who had set up an entire Ministry of Perfumes, and the Shreshtis in his domain prolifically imported aromatic raw materials and copious barrels of exquisite perfumes from Persia, Portugal, etc.

Finally, on the basis of my limited studies in this subject, I can say with some confidence that a study of corporate and business life in ancient India is also an invitation to an ennobling penance. The names and accomplishments of some eminent businessmen have been preserved in royal edicts, epigraphs and grant records. These are the stories we must unearth, popularise and prescribe them as reading material for our children. If they reveal anything, it is this: that our business class was distinguished not just for their financial acumen; they made tons of money, yes, but they went far beyond this ken. In peacetime, they contributed to society and nurtured culture. In times of crisis, they stood with their chest thrust forward. When they were profoundly moved, they donated all they had and renounced the world in quest of higher callings.

The history of corporate and business life of Bharatavarsha is no less exalted than its spiritual history, which is but natural.

Think about it.

Series concluded

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.