- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

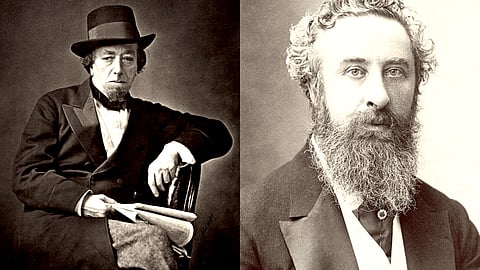

Left: Benjamin Disraeli | Right: Lytton

Benjamin Disraeli: Prime Minister of England

Lord Salisbury: Secretary of State for India

Lord Lytton: Viceroy of India

Upendranath Das: Drama Director

Amritalal Bose: Manager of Great National Theatre

TODAY, BENJAMIN DISRAELI’S NAME PRIMARILY evokes a foggy recollection as someone who was well-known for his prose style. Until the late 1970s or early 1980s, his fat novel Sybil was a prescribed text in the non-detailed English syllabus for undergraduate students of India. In his own time, outside the literary world, Disraeli commanded two terms as Prime Minister of England and singlehandedly turned around the fortunes of the Conservative Party to the extent that it became synonymous with the unmitigated evil that was the British Empire. He of course, phrased it differently: the Conservative Party was the grandest celebration of the glory and power of the British Empire whose crown jewel undoubtedly was India. With all the honesty that bigotry and racism can inspire, Disraeli genuinely believed that colonial Britain was actually giving “good government” to India. This in turn led an Indian scholar to make this delicious remark of sarcasm:

In this grand endeavour of empire-scale plunder and oppression, Disraeli was ably assisted by two fellow-racists and cupbearers. The first was his protégé, “Lord” Lytton, the viceroy of India from 1876-80 and presided over the Great Famine of 1876-78, which wiped out a whopping ten million Indians in a substantial geography spread across the presidencies of Madras and Bombay and the Princely States of Mysore, Hyderabad, and large parts of the Central Provinces, North Western Provinces and Punjab. The second was “Lord” Salisbury who was Secretary of State for India from 1874-78.

Geographical Extent of the Great Indian Famine of 1876: Wikipedia

Even as hunger and starvation were killing off Indians like flies, the Lytton-Salisbury duo were busy mining their brains and excavating India for more effective and ruthless means to further bleed the country and enrich their empire of venality. The worst of these was the needless Second Anglo-Afghan War that Lytton unleashed for two long years (1878-80), notable for British gruesomeness and industrial-scale barbarism. We get an idea of the nature of this British brutality when we learn the fact that even folks back home in England were disgusted with Lytton. That is saying a lot given the yet-uncured savagery inherent in these descendants of cavemen. Yet, his country not only forgave this war criminal but actually celebrated it by installing a permanent exhibition in Knebworth House “dedicated to his diplomatic service in India.”

Needless, Lytton couldn’t act without the express instructions of his bossman, Benjamin Disraeli. The Afghan misadventure cost Disraeli his Prime Ministerial seat; he had to resign in disgrace. And he naturally took Lytton down with him. Lytton was recalled to England and in the perfidy masquerading as honourable service that only the British have patented, an earldom was specially created for him. He was now rehabilitated as Earl of Lytton and not only remained unscathed in the world of British politics but thrived as before. In 1887, he was appointed as Ambassador to France, an elevation that enthralled him. In his own words, “I am enjoying myself, once more back in my old profession.”

BENJAMIN DISRAELI’S ORDER TO INVADE Afghanistan was prompted by England’s anxiety about Czarist Russia’s eye over Afghanistan. The Afghanistan of 1870s was a semi-autonomous country ruled by the shrewd Amir, Sher Ali Khan, a son of the more famous Dost Mohammad Khan. Sher Ali Khan’s hatred for the British swung him into Russian arms, and eventually led to his downfall and destruction at British hands.

In our context, the funding of the second Anglo-Afghan War is the primary concern: following the British SOP, Disraeli funded it both by increasing existing taxes and inventing new ones. The major theatre for these taxes – basically, blood money - was Bengal and to a good extent, Bihar.

Disraeli’s moves which culminated in the Afghan War had arguably begun in 1874, when he assumed Prime Ministerial office for a second (non-consecutive) term. The then viceroy of India, “Lord” Mayo increased income tax from one percent to three-and-half percent in Bengal and Bihar. This was in addition to a new tax, the road cess introduced earlier in 1871 by George Campbell. And now, “Lord” Salisbury, Disraeli’s lieutenant, continued the older scorched-earth British policy of annihilating Indian textiles by extending protective duty on Lancashire cotton. The sheer heartlessness of all this was the fact that it was inflicted during the Great Bengal-Bihar Famine of 1874.

And the protests that began to stir in Bengal first came in trickles and eventually reached several dramatic climaxes. Literally. Some were bloody and in hindsight, were well-deserved by the British.

On September 20, 1871, Justice Norman, the acting Chief Justice of the Calcutta High Court, notorious for passing severe sentences singling out Wahabis, was fatally stabbed by Abdullah, as he was descending the steps of the Calcutta Town Hall. Norman succumbed to the injuries the next day.

On February 8, 1872, as “Lord” Mayo was inspecting the “convict settlement” (this later became the full-fledged, infamous cellular jail) in the Andamans, the Afghan prisoner Sher Ali Afridi attacked him with a lethal knife. Mayo bled to death. Afridi had earned distinction by serving in the East India Company army and the British had done this to him.

Aside, it is a glaring shame that a court complex named after Mayo in Bangalore still retains its name.

Mayo’s brazen assassination sent shockwaves throughout England and repression of Indians especially in Bengal, expectedly increased.

A companion rebellion of sorts occurred in the Princely State of Baroda. As Resident of the State, Colonel Phayre unleashed his meddlesome antics against Maharaja Malhar Rao Gaekwad. Unfettered and unrelenting meddling was a trait shared by a majority of, if not all, British Residents. A favorite tactic was to write an unending stream of complaining letters against the Maharajas to the Viceroy. In reality, the Resident was a spy cloaked as an administrative supervisor, and commanded tyrannical powers. In fact, a comprehensive volume akin to a Rogues’ Gallery can be written about several of these Residents. The friction between Phayre and Malhar Rao eventually reached a climax. Unable to bear these serial humiliations, Malhar poured arsenic and diamond dust in Phayre’s sherbet. However, luck favoured him and on April 10, 1875, the selfsame “Lord” Salisbury deposed Malhar Rao Gaekwad and exiled him to Madras.

The outrage against such a shabby treatment of a reigning Maharaja echoed in faraway Calcutta. In the pages of the fire-spewing Amrita Bazaar Patrika. It thundered on January 23, 1875:

On their part, the British Government in India had realized that they were hurtling from blunder to blunder, all of which they had created. But monsters like Benjamin Disraeli and Lytton came from the school of racism, loot and repression. Nothing would melt their hearts. Far from it, every act of opposition from Indians doubly steeled their resolve to crush the bloody natives. Greater the opposition, bloodier the pulping.

A CLOSER STUDY OF BENGAL of the 1870s decade uncovers truly pivotal discoveries. This was the era immediately preceding the burst of Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and Swami Vivekananda on the national scene. On the British side, memories of 1857 were still fresh and still had the potential to give them the shudders. On the Indian side, another 1857 was impossible but their unyielding spirit of independence continually birthed creative methods of resistance.

One such method was staging plays and dramas specifically aimed at making the British squirm and to infuriate them without using violence. A measure of the enormous success of this method directly led to the creation of a draconian law, which unfortunately has not been fully repealed even to this day: 146 years after it was created, 75 years after India attained a questionable independence.

Passed on December 16, 1876, the legislation had a no-holds-barred title: The Dramatic Performances Control Act of 1876 (Act XIX).

That story and its aftermath will be narrated in the next episode.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.