- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

George Viscount Valentia’s 1809 book Voyages and Travels (1802–1806) is a richly detailed, highly valued primary source on early-19th-century India. Valentia asserts British racial superiority and sees Hindus as superstitious yet benefited by British rule.

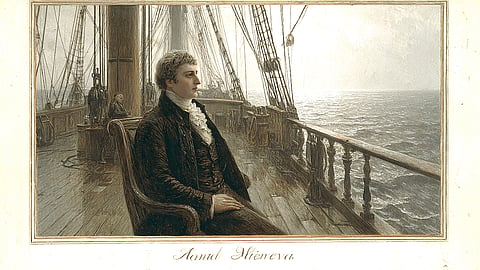

ON JUNE 5, 1802, George Viscount Valentia climbed aboard the Minerva at the Downs off the east Kent coast, embarking on a four-year-long voyage that first took him to India, then Sri Lanka, the Red Sea, Ethiopia and Egypt.

Back in England in 1806, Valentia compiled his experiences, which were published in 1809 in three thick volumes entitled Voyages and Travels to India, Ceylon, the Red Sea, Abyssinia and Egypt, in the years 1802, 1803, 1804, 1805, and 1806. He posthumously dedicated the work to Richard, Marquis Wellesley. It opened to instant public acclaim in England. For a good reason.

Throughout his sojourn, Valentia had maintained a journal in which he recorded every minute detail almost on a daily basis: the weather, the changing colours of the clouds, the whimsical temperament of the sea, the contours of roads and hills and crevices and rocks, the tinge of leaves and the thickness of trees, peculiarities of harvest and livestock, the formation of garrisons and forts, the diet, dress, hygiene, manners and etiquette of people, sights, smells and noise of cities and towns and nuances of economy, wars and history. Each entry is dated, thereby providing a continuous chronological narrative.

Valentia’s meticulousness is truly admirable but what really elevates the standard of the work is the gamut of his learning, his powers of observation and his capacity for contextualisation. Thus, it is not a mere travelogue but a rather erudite, first-hand chronicle that spans the politics, society and culture of three continents set in a radioactive period of history.

As an exhaustive primary source, it is indispensable to historians; as a study in characters of the chief protagonists of the era, it is a litterateur’s treasure; as a testimony to the nonchalant manner in which the Mughals and Hindu rulers bartered away India’s freedom like slices of a cake, it is a tragedy of epic dimensions, and as a personal treatise of comparative cultures, it is quite instructive. Its enduring value can be gauged by the high prices that its first edition still commands at auctions — up to £1000.

Valentia’s Voyages and Travels is also imbued with most of the defining flaws of colonial literature. There is a pronounced contrast in his observations of India vis a vis his 17th and 18th century predecessors, who wrote as traders, adventurers, ambassadors, physicians, missionaries or simply as inquisitive men documenting the results of their curiosity regarding an alien land and people.

Viscount Valentia wrote in the spirit of a conqueror.

When he arrived in India, half a century had elapsed since the Battle of Plassey. The Great Maratha Empire had suffered an irreversible setback 41 years ago and was now headed for extinction. The inept, depraved and blind Mughal king, Shah Alam II had become a quasi slave of the East India Company. Tipu Sultan, the tyrant of Mysore, had met his maker three years before Valentia arrived. Wellesley, now at the zenith of his power, was indiscriminately gobbling up the Princely States by deploying his notorious Doctine of Lapse. The Portuguese and the Dutch were not even a pale shadow of their former influence. The French too, were being rapidly ejected. The onward march of British dominance in India was unstoppable. All these simply proved an established truth — the innate superiority of the British race.

This conquistadorial spirit and tone is the ādhāra-śruti — the base note of Valentia’s corpus. He writes not as a curious or humble knowledge-seeker but as a haughty, self-assured victor dissecting an inferior subject-race on a surgical table. His fawning adulation of the reprehensible Wellesley is emblematic of this imperial spirit:

This spirit is also underpinned by the Biblical and evangelist bias, which regards Hindus as heathens and superstitious idol-worshippers who have no religion and thus need to be saved.

A hardened creation of this milieu, Valentia is also a sincere exponent of the White Man’s Burden and earnestly believes that it was British benevolence that saved the “Hindoos” and gave them the full freedom to practice their revolting superstitions. Yet, on occasion, he admires the guileless simplicity of the Sanatana way of life and shows genuine respect for things that Hindus consider as sacred.

On the other side, Valentia is unsparing of the Mughal rule which had reduced India into a wasteland. He reserves special contempt for the violent intolerance embedded in the heart of the Islamic scripture and the intrinsically oppressive character of a Muslim regime.

Valentia’s brief stay in Varanasi is perhaps one of the most truthful expositions of this Hindu-Muslim contrast and prolonged conflict written by an Englishman.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.