- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

AFTER ABOUT A HALF HOUR OF TRAVELLING southwards from Kanchipuram towards Vandavasi, we reach Koolamandal, one of those typical nondescript villages. Once a flourishing hub of piety and prosperity sustained by a vibrant Sanatana society. Now unknown, uncared for…remembered only during elections.

Koolamandal (its earlier name: Kulambandal) was one of the cynosures of the grand Chola Empire. Its formerly magnificent — and now restored Gangaikondacholeesvarar Temple was built by the formidable Rajendra Chola I in 983 CE under the guidance of his spiritual Guru, Ishana-Shiva Pandita.

A mile-long eastward journey from Koolamandal leads us to another site of civilisational amnesia and cultural apathy. This is the Ukkal village. You would look at me strangely if I told you that for about three unbroken centuries, Ukkal reigned as one of the exemplars of village administration that had touched the summit of perfection.

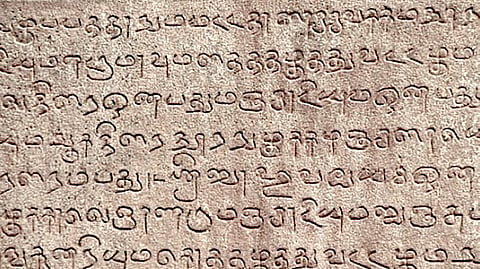

Even this glorious heritage would have been lost to us but for the diligence of Sri K.V. Subrahmanya Iyer who in 1893 discovered seventeen inscriptions in the ruins of an ancient Vishnu temple. Of these, only fourteen were reasonably well-preserved. Of these fourteen, only twelve give us precise details of how the aforementioned village administration functioned.

Sri Iyer sketches a brief portrait of the heartbreaking condition of that temple: “Of the shrine itself, only the lower portions remain standing, and the mandapa in front of the shrine threatens to collapse at any moment.” After much tedious searching, I could identify the present name of this temple as the Arulmigu Bhuvana Mangala Perumal Temple.

The inscriptions cover the period from the eighth to the eleventh century spread over the suzerainties of the late Pallavas, the Rashtrakutas and the Cholas. They inform us that this Vishnu Temple was originally called Puvanimanikka (i.e., Bhuvanamanikya) Vishnugriham. Rajaraja I referred to its deity as the Tiruvaymolidevar (i.e., the Deity of the Tiruvaymoli), a direct reference to the Nalayiraprabandham composed by Nammalvar.

At various points in its long history, Ukkal was also known as Utkar, Utkal, Sivachulamanimangalam, Vikramabharana-chaturvedimangalam and Aparajita-chaturvedimangalam (a reference to the Pallava King, Aparajita).

WITHOUT EXCEPTION, EVERY HINDU EMPIRE faithfully adhered to the ancient dictum of Santana statecraft that the lowest unit of administration must have the maximum autonomy. Interference from the central government was kept at the barest minimum as we have seen in this ennobling story of the Yogic village of Sorade. We notice the same feature in Ukkal as well.

In fact, a close study of these fourteen inscriptions opens up highly illuminative insights regarding the setup, constitution and functioning of village administration in South India. Its contents attracted the attention of no less a stalwart than R.C. Majumdar who wrote quite extensively about their value…sitting far away in Calcutta.

Ukkal was governed by an assembly known as the Sabha or Mahasabha, an unbroken administrative inheritance from the Sabhas and Samitis of the Vedic Era. The village assembly was subdivided into various committees tasked with specific functions. Committee members, technically known as Perumakkal (Distinguished Men), were elected each year. Transactions of the assembly were scrupulously recorded in registers and ledgers and other official books by an officer known as the Madhyastha (Arbitrator). Its accounts were maintained by the village accountant known as the €™Karanattan (its Telugu variant is Karanam, a familiar surname in south India). Sometimes, the Madhyastha also performed the duty of the Karanattan.

Here is the list of Committees constituted for Ukkal:

1. Distinguished men elected for the overall village assembly

2. Distinguished men elected for charities

3. Distinguished men elected for the village tank

4. Distinguished men elected for gardens

5. Distinguished men who manage the miscellaneous affairs of the village

If this sounds similar to the more renowned Uthiramerur inscription, it is because it is similar. The difference is only in the details. In other words, the constitution of such village assemblies differed in different localities and at different periods in history. Specific aspects of administration in each village were periodically upgraded or modified based on changed conditions or needs.

LET’S HEAR IT DIRECTLY from the horse’s mouth. The following short summary of twelve inscriptions discovered at Ukkal, offer firsthand evidence of the specifics of village administration. The numbers indicate the inscription number.

1. The Assembly of the village received a deposit of an amount of gold from one of the commissioners ruling over another village on the condition of feeding twelve Brahmanas and doing other useful works from the interest on this sum.

2. A certain person donated a plot of land to the great Assembly on the condition that its produce should be utilised for supplying the God with a stipulated quantity of rice. The inscription concludes as follows: “Having been present in the Assembly and having heard their order, I, the Madhyastha wrote this.”

3. A certain person had purchased a plot of land from the Assembly and assigned it to the villagers for the maintenance of a flower garden.

4. On receipt of a plot of land, the Assembly undertook to supply paddy to various persons engaged in connection with a cistern which the donor had constructed to supply water to the public.

5. The Assembly undertook to supply an amount of paddy per year by way of interest of a quantity of paddy deposited with them. The Perumakkal elected for the year would cause the paddy to be supplied.

6. A meeting of the Assembly, including the Perumakkal were elected for the management of charities and the commissioners in charge of the temple of Sattan in the village. The Assembly assigned a daily supply of rice and oil to a temple. The Perumakkal elected for the supervision of the village tank shall be entitled to levy a fine of (one) kalanju of gold in favour of the tank fund from those betel-leaf sellers in this village, who sell betel-leaves elsewhere but at the temple of Pidari.

7. The Assembly accepted the gift of an amount of paddy on the condition of feeding two Brahmanas daily out of the interest on this amount.

8. The Assembly has received a royal order authorising the village to sell lands on which tax has not been paid for two full years. Accordingly, these lands have become the property of the village.

9. This is the record of a sale of a plot of land by the village Assembly, which was their common property, plus a sale of five water levers, to a servant of the king who had assigned this land for the maintenance of two boats plying on the village tank.

10. The great Assembly — including the Perumakkal who were elected for the year and the Perumakkal elected for the supervision of the tank — being assembled, assigned, at the request of the manager of a temple, a plot of land in the fresh clearing for various specified purposes connected with the temple.

11. The village Assembly grants a village to a temple, including the flower garden, for the requirements of worship there. The terms of grant include the following: “We shall not be entitled to levy any kind of tax from this village. We, the Perumakkal elected for the year, we, the Perumakkal elected for the supervision of the tank, and we, the Perumakkal elected for the supervision of gardens, shall not be entitled to claim forced labour from the inhabitants settled in this village. This is confirmed at the order of the Assembly. If a crime or sin becomes public, the God (i.e., the temple authorities) alone shall punish the inhabitants of this village. Having agreed thus, we, the Assembly, have engraved this on stone.”

12. The son of a cultivator in the village assigned a plot of land in the neighbourhood. From the proceeds of this land, water and firepans had to be supplied to a mandapa frequented by Brahmanas. Further, a water lever was constructed in front of the cistern at the mandapa. The Perumakkal who manage the affairs of the village in each year shall supervise this charity.

CLEARLY, THE UKKAL INSCRIPTIONS give us a rather comprehensive and unambiguous idea of the powers and functions of the village Assembly, and the perfection they had reached in administration. Nothing was left to chance or individual whim. Annual elections prevented monopolies and concentration of power. Every transaction was written down to the last detail and publicly ratified.

The macro dimension of Hindu statecraft and administration also reveals the fact that village assemblies were regarded as inextricable parts of the constitution of the country. As we mentioned earlier, they were entrusted with the entire management of the village in a truly autonomous fashion. Sabhas and Mahasabhas were absolute proprietors of village lands and they had full authority to create fresh clearings. They owned corporate property which they could sell for public purposes such as supplying the necessities of temples, digging wells and growing gardens. In essence, the village assembly exercised all the powers of a state within its own sphere of activity. In return, it had to deposit annual revenues to the imperial treasury and maintain peace and order and prevent rebellious or anarchist feelings.

In some cases, the Mahasabha of one village exercised jurisdiction over other villages. Inscription 11 cited above presents one such example. It shows that the Ukkal Assembly owned another village situated about three miles away. This village was given as a tax-free grant in order to provide for the necessities of a temple in Ukkal itself. This is how the inscription reads:

We, the assembly of Sivachulamanimangalam, alias Sri-Vikramabharana-chaturvedimangalam [Ukkal] ordered as follows: “To the god of the Puvanimanikka-Vishnugriham in our village shall belong, as a divine gift (deva-bhoga), the village called Sodiyambakkam, a hamlet (pidagai) to the north of our village, including the great flower-garden which belonged to this (temple) previously. The site of the village, the tank, the wet land, and dry land, and everything within its limits, on which the iguana runs and the tortoise crawls, for the worshippers of the god of his Puvanimanikka-Vishnugriham, for the requirements of the worship, for oblations (Tiruvamridu) at the three times of the day, for two perpetual lamps, for rows of lamps at twilight, for festivals, for the bathing of the idol at solstices, equinoxes and eclipses, for offerings (sribali), for supplies to the store-room of the temple, and for all other purposes. We shall not be entitled to levy any kind of tax from this village… If we utter the untruth that this not as stated above, in order to injure the charity, we shall incur all the sins committed between the Ganga and Kumari. We, the assembly, agree to pay a fine of one hundred and eight kanam per day, if we fail in this charity through indifference.

To round off this essay on a depressing note, the following photographs show the present condition of Ukkal.

If the blunt truth should be told bluntly, the primary sources of Hindu history—such as the Ukkal inscriptions—reveal a completely different picture about our understanding of our own history. Clearly, the Ukkal inscriptions showcase a high degree of administrative sophistication and perfection both in theory and practice, attained in an era sans technology, where primacy was placed on the human element.

Given all this, I remain dazed when I hear “educated” Hindus nonchalantly claiming that ”Hindus have no sense of history,” “we have not preserved institutional memory,” and accompanying gems of such flagrant ignorance.

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.