- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

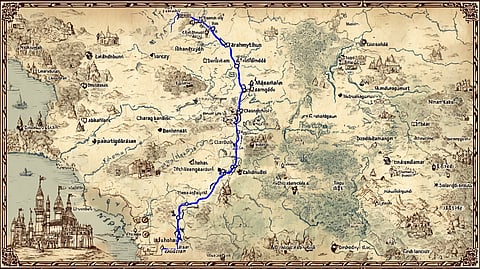

Throughout Valentia's journey from Calcutta to Bhagalpur, his journal reflects colonial arrogance, admiration for British conquests, and disdain for local customs, while valuing its historical insights into early 19th-century British rule in India. The narrative underscores colonization as a system of divine-like luxuries for the British elite.

JANUARY 27, 1803.

Marquess Wellesley prepares a tentative travel plan for Viscount Valentia. Keeping in mind the “advanced season,” he advises Valentia to “proceed immediately” to the “upper provinces”: Bihar, Awadh and much of what is today called Uttar Pradesh. Wellesley earnestly assures that he would exert his entire official machinery in Valentia’s service.

He repeatedly begged me to point out in what manner I wished for his assistance; and assured me, that I should have it in the fullest manner, both as to passports, and even escorts when necessary…he [would] certainly give me the precedency of every body, except the immediate members of the executive government.

The marvels of the English peerage system are on practical display throughout Valentia’s stay in India; by rank, Valentia as an Earl, is inferior to Wellesley, a Marquess. Yet, the indulgent treatment he receives in India is sensational in both its tenor and detail.

But almost a month elapses before Valentia can begin his journey, which would terminate at Lucknow. He falls sick for a week with a severe cold. Then he squanders his days away by attending dinners and receptions and other social events, meeting high-ranking officials and judges and doctors and botanists. Needless, each of these gentlemen is keen to be in his good books.

For these several days past my time has been most completely occupied in receiving and paying visits, and in a round of dinners. My reception has been such as I had every reason to expect from the character of my countrymen in the East.

Valentia has one last dinner meeting with Wellesley on February 20. In a sense, it hints at the prospects of a mutually beneficial partnership after Wellesley returned to England.

After dinner I had a long private audience, and quitted his Excellency, most deeply impressed with a sense of his past kindness and his future good intentions towards me. No mean suspicions of my motives for visiting this country were harboured, but a manly, open, and generous assistance was afforded me in the acquisition of every political information, with facility and pleasure.

FEBRUARY 21, 1803. 11 A.M.

Valentia begins his riverine journey towards Lucknow from the Chitpore Ghat in a modest boat covered with reeds. He is greatly upset at this; he had anticipated a vessel similar to the state barge that had originally received him.

He first disembarks at Chinsura and travels by palanquin to Hooghly and spends the night in the bungalow of an official named Mr. Brook.

From here onwards, Valentia travels by both river and road and travels “always at night and halt(s) in the day, as the scenery in Bengal is uninteresting from the uniform flatness of the country.”

His first major destination is Varanasi.

Wellesley has arranged every comfort and luxury. Valentia’s palanquin is borne by eight bearers, three mussals (“link boys”) and three men who carry his luggage. His palanquin is “fitted up with Venetian blinds, and pillows for sleeping, and were long enough to allow of our lying in them at full length.” Small wonder that Britain felt such intense anguish for having to relinquish India. The colonisation of India was not merely a commercial enterprise but an irreplacable system that allowed the perpetual enjoyment of heavenly delights on a large chunk of the earth. Colonial eminences were verily Gods who had condescended to visit the mortal world.

Valentia travels 800 miles and more in this style.

His next stop is Palashi and the moment he steps on its soil, Valentia is ecstatic. It is a “place celebrated in history for the victory obtained by Lord Clive…From that period we may be considered as masters of Bengal, and to that victory we in fact owe the vast empire we now possess.”

From Palashi, he travels to Berhampore, which was “one of the six great military stations in these provinces.” He stays at the residence of a certain Captain Parby. Indeed, Wellesley has planned Valentia’s itinerary and logistics with military precision. Each halting place is either a cantonment or the mansion of a lofty Company officer. Safety is paramount; despite being in absolute control of Bengal, Wellesley is paranoid; an outbreak of even a minor revolt could occur any time.

Valentia as usual, receives splendid treatment at each “changing place” and gives a brief description of its climate, geography, history and its current condition under the British yoke. The value of his observations in reconstructing the history of British colonial rule is quite substantial.

Murshidabad, five miles away from Berhampore, catches Valentia’s attention. Its Nawabi, begun by Murshid Quli Khan and lost by Siraj-ud-Daulah to the British, is now helmed by Munni Begum, the widow of Mir Jaffar and the real power behind the throne. Robert Clive and Warren Hastings had honoured her with the title, Mother of the Company as a conciliatory gesture.

Clive had extinguished the Murshidabad Nawabi but she still retained a fabulous amount of personal wealth and controlled the “royal” household with a dictatorial grip. She was ninety-three years old when Valentia wrote his assessment of her multifarious talents; he leaves nothing to the imagination.

She is excessively rich, and still retains her intellects in full vigour… A history of her life would include all…the vicissitudes that can happen to an individual, even in Asia… her son reduced to be a pensioner… She, however, has still the rank and property of a princess… The allowance…would be amply sufficient for their maintenance with a proper degree of dignity, were it not for the prodigious increase of their numbers, and the improvidence that seems to be inherent in the Mahomedan character… It was my intention to have paid a visit to the old lady, in order to hear her voice, (which, I understand, is uncommonly shrill, and which she sometimes raises to its highest key)…

Valentia’s observation regarding the fecund breeding and financial profligacy of the Muslim society is a common theme underlying his journal.

Before departing from Berhampore, he gives a frank but disturbing picture of the rampant destruction of Bengal’s wildlife by the East India Company.

During dinner we had a chorus of jackals around the house. This, and the fox, are the only wild animals left in the island of Cossimbuzar: formerly it was very full of tigers and leopards, but the increase of population, and the rewards, paid by the Company, have here completely exterminated them, and much thinned them in other parts. Ten rupees are paid for the head of a full grown tiger, and five lor a leopard, or tiger's cub.

Needless, the decapitated heads of these Bengal tigers eventually adorned the sumptuous living rooms of East India Company officials when they returned to England.

ON FEBRUARY 25, Valentia finds himself in Jangipur, which was then a flourishing hub of silk manufacture and trade. The next day, he is in Rajmahal (now in Jharkhand), “the last halt I was to make in the province of Bengal.”

From here, the journey to Bhagalpur takes about two days. The route passes through a maze of forested hills, ravines, crevices and treacherous passes which are so narrow that Valentia’s palanquin-bearers face great difficulty. Valentia is sufficiently furious as to launch a tirade against the unquenchable greed of the Company.

On the morning of February 27, Valentia awakens to the bland sight of a vast plain covered with “European grain.” He is 18 miles away from Bhagalpur. After covering four miles, he encounters a group of convicts building a road. Like so many such precedents, this practice of using convicts for public infrastructure work was begun by the British; it persists till date; the stately Vidhana Soudha in Bangalore was built by the labour of 5000 prisoners.

As Valentia approaches Bhagalpur, he spots a “monument, resembling a pagoda, erected to the memory of Mr, Cleveland.” This is the Cleveland Memorial at Tilaka Manjhi, now a surburb in Bhagalpur. From Valentia’s narrative, we get a picture of affection and respect that Augustus Cleveland — a Collector and Judge of the districts of Bahgalpur — had commanded in the region.

…the Aumlah [revenue officers] and Zemindars of the Jungleterry [forested lowlands] of Rajahmahal, who, before his time were a race of savages, and whom, by conciliatory means alone, he induced to place themselves under the protection of the British Government.

The marble plaque erected before the memorial is simultaneously an eulogy of Cleveland and a boast of the benevolence of the British empire.

"To the Memory of Augustus Cleveland, Esq.

Late Collector of the Districts of Bhaugulpore and Rajamahall,

Who, without bloodshed or the terror of authority,

Employing only the means of conciliation, confidence, and benevolence,

Attempted and accomplished,

The entire subjection of the lawless and savage inhabitants of the

Jungleterry of Rajamahall,

Who had long infested the neighbouring lands by their predatory

Incursions,

Inspired them with a taste for the arts of civilized life.

And attached them to the British Government, by a conquest over

their minds;

The most permanent as the most rational of dominion."

At Bhagalpur, Major Shaw receives Valentia and treats him to a lavish dinner at his bungalow.

At 9 P.M., Valentia resumes his journey and finds himself in the “house of Captain D’Auvergne” in Munger at 7 A.M. Unsurprisingly, he experiences a “very hospitable reception.”

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.